Book: Patents, Cloaks & Daggers ~ Inside the Secretive Patent Trade

CONTENTS

- Introduction

- Check your Fundamental Understanding of Patents

- Why Buy a Patent?

- Why Sell a Patent

- A Market Driven by Litigation

- Few Commercialization Options for Inventors

- The Patent Marketplace

- Patent Litigation Attorneys

- Non-Practicing Entities (“NPE’s”)

- Which Patents Sell?

- Selling Pending Applications

- Selling International (Non-U.S. Patents)

- Why there’s Safety in Numbers for Patents

- Only One in a Thousand Patents Are Litigated in Court

- Where to Find Patents to Buy

- Patent-Packed Products and Single-Patent Product

- Patent Valuation

- Patent Sale Transactions are Cloaked in Secrecy

- Claims Charts & Evidence of Use

- Identifying Which Patents to Buy—The Evaluation Process

- Identifying Which Patents to Sell—Prioritization

- Patent Licenses & Encumbrances to Clean Title

- Skeletons in the Closet—Or Scary Documents in the Patent Files

- Does the Seller Actually Own the Patent He’s Selling?

- The Patent Sale Transaction

- “Unclean Hands” in the Patent Trading Process

- The Patent Seller’s Broker

- The Patent Buyer’s Broker

- What Does the Future Hold for the Patent Trade?

- About the Author

Introduction

This book explains the role of patents in business today, discussing the strategies adopted by corporate decision-makers involved in various aspects of the patent wars with special emphasis placed on the high-tech sector and the patent trading marketplace.

The patent trade is big business today, involving billions of dollars in transactions. Featuring trolls, war chests, cloaks and daggers, this secretive business can be considered somewhat bizarre to outside observers.

Core to understanding the patent business is an appreciation of the nature of patents. A patent is a weapon of litigation, a right to ask a court to award damages for infringement, and prevent future infringement by blocking the sale of infringing products. Although inventors often prize their patents as trophies of technical prowess, patent industry insiders appreciate that the only substantive right a patent holder enjoys is the right to exclude others from unauthorized practicing of the invention. A patent is more of a dagger than a shield.

As patents are weapons, and patent wars are raging across the technology sectors, trading in patents takes place under a cloak of secrecy. Buyers, in fear of triggering lawsuits and punishing damages awards, operate in stealth mode, often shielded by lawyers or brokers acting on their behalf. Brokers and other intermediaries act as arms dealers to the patent wars. Throughout this book, you will see that secrecy and confidentiality concerns drive some of the bizarre features of the patent trade.

It would be difficult to find a marketplace where the spread of price expectations between buyer and seller is so wide. Patent holders, inexperienced in patent selling or patent litigation, are often under the mistaken impression their patents are highly valuable assets when in the vast majority of situations, the patents are unsellable, or of very little value. In reality, so few patents are both infringed and capable of withstanding the rigors of litigation that finding patents meeting the quality standards required of buyers is like finding a needle in a haystack.

This is an industry where the value of an asset can evaporate in the blink of an eye, when issued patents are invalidated on a finding of prior art, or one of a myriad of reasons. This is an industry driven by litigation where lawyers play in instrumental role, where trolls are feared and despised, and where many o argue the whole system is broken.

Patent holders come in all shapes and sizes. Some products are made of one single patented invention, while other products are comprised of hundreds of thousands. We will explore how the patent strategies adopted by companies marketing single-patent products differ from the strategies adopted by those selling patent-packed products.

If you’re reading this book because you hold a patent and you’re wondering what to do with it, you’ll find the answer depends on whether you’re a huge corporation and the field of the invention involves patent-packed products or single-patent products. Some products, such as smart phones, comprise hundreds of thousands of patented inventions and involve patent wars with billions of dollars at stake. Unless you have a war-chest of funds (measured in tens of millions of dollars) and an army of lawyers at your disposal, you will not be taken seriously in this type of business and your best option might be to sell your patents to one of the larger players. If, on the other hand, you’re marketing a product comprising predominantly your own patented invention, you might want to hold on to the patent so you can use it to deter competitors copying your design.

The patent strategies for complex patent-packed products, such as electronics, software and high-tech devices are totally different from the patent strategies adopted for single-patent products like consumer gadgets and pharmaceuticals. The strategic value of a patent used in a smart-phone application is very different from the strategic value of a patent used in a paper clip. Where a single paper clip patent might hold the power to deter companies copying the paper clip design, no smart phone patent will ever deter companies manufacturing smart phones. You might be able to avoid patent infringement if you’re marketing paper clips, but it’s impossible to compete in the electronics or software business without infringing patents. Your best defense in that situation is to instill fear in your opponents by assembling a large number of dangerous patents and employing a battalion of battle-scarred lawyers.

If you’re an inventor, proud of your patent, and you learn you’re unable to commercialize your patent or to sell it, you may find the realities of the patent market, as exposed in this book, to be something of a disappointment. Unfortunately, many inventors discover the real value and opportunities represented by a patent some time after they have already invested in patent filing and attorney fees. However, I ask you to consider this: Your contribution to the advancement in science has been found worthy of a patent grant and your achievement is on record and available for the world to see. By reading your patent, scientists, inventors, technologists and product developers in years to come will be able to learn from your innovative work. If your invention is unsuitable for commercialization today, perhaps advances in technology will make commercialization a possibility at some point in future. Your patent might be impossible to commercialize or to sell, but it has an enduring value to science and society.

In order to make this book unappealing to any readers whatsoever, I have inserted a few simple math calculations that will deter any lawyers, and I have included some legal terms that will surely deter any non-lawyers. Seriously, the math is very simple and the legalese is translated into normal English that should be easy to understand. I hope the fear of arithmetic and legal jargon (like the word “court”) does not deter you from reading on and learning about this cloak and dagger industry.

If you’re still reading at this point, and haven’t been scared away by the realities of this strange hidden world of trolls, legalese and multi-billion dollar wars, I hope you enjoy the book and find it useful.

CHECK YOUR FUNDAMENTAL UNDERSTANDING OF PATENTS

Imagine you sold bicycles and had a patent awarded on your inventions for a novel, useful bicycle design. What does this patent allow you to do? If you’re thinking perhaps, as many people do, that your patent allows you to implement the invention and sell your new bicycle design without worrying about being sued for patent infringement, then you would be wrong. Your patent is not a shield or a license to build and sell your invention. The patent is a license to use the courts to inflict injury on your competitors, discouraging others from building and selling your invention without your approval. If you do build the bicycle design according to your patent, you will likely be infringing patents held by others on components such as brakes, gears, seats, handlebars and wheels. Your bicycle design patent does not protect you from infringing patents in your own bicycles, but does provide you with a weapon you can use to attack competitive bicycle manufacturers that copy your design without your approval. If a competitor attacks you with a patent infringement suit for implementing their patented handlebar design in your bicycles, you can counter-sue them for infringing your patented design in their bicycles.

Patents have been around for hundreds of years, and have changed relatively little during this time. In 500 BC, the (then) Greek city of Sybaris decreed: “Encouragement was held out to all who should discover any new refinement in luxury, the profits arising from which were secured to the inventor by patent for the space of a year.”1 Since the time of Ancient Greece, other states all over the world have followed suit and consistently recognized the need to reward inventors with exclusive rights to their inventions for a period of time. A patent is essentially a deal between the inventor and the state whereby the state offers inventors the right to exclude others from copying their inventions for a period of time in return for the inventors publishing details of how the inventions work. Patent rights were incorporated into the original U.S. Constitution2, stating: “The Congress shall have power…To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries…”.

Since their inception, patents have been based on the notion of exclusivity. The right to exclude others from practicing the invention is bestowed on the inventor when a patent is granted, and many people believe the right to exclude others is the only substantive right associated with a patent. The process of excluding others is provided by the courts, hence involves litigation. So the assertion of patents requires legal proceedings—and patents are essentially weapons of litigation. A patent can be considered a ticket, or pass, providing access to the court system, but it can only be used when others copy the patented invention in their products.

I may be laboring the point, but once you accept the realization that a patent is essentially a right to sue infringers, the role of trolls and the various strategies adopted by combatants in the patent wars suddenly make sense.

1Charles Anthon, A Classical Dictionary: Containing An Account Of The Principal Proper Names Mentioned in Ancient Authors, And Intended To Elucidate All The Important Points Connected With The Geography, History, Biography, Mythology, And Fine Arts Of The Greeks And Romans Together With An Account Of Coins, Weights, And Measures, With Tabular Values Of The Same, Harper & Bros, 1841, p. 1273.

2U.S. Constitution, Article One, Section 8(8).

Granted Patents

Once a patent application has been examined, found to meet all the criteria laid down by the state, and fees have been paid, the patent is granted and the exclusive rights associated with a patent come into force. When I refer to “patents” in this book, I’m essentially referring to granted patents, not pending applications. Until the patent is granted, the right to exclude others from practicing the invention has not yet come into force.

Patents are country specific, and a patent granted by the U.S. patent office covers the United States only. A patent granted by the French patent office covers only France. Although there are international applications, granted patents are specific to, and restricted to one country or state.

All patents expire after a period of time, allowing others to freely copy and practice the disclosed inventions. In the U.S., the patent term is now 20 years from the date of the filing of the application, after which the invention goes into the public domain.

The granting of the patent by the patent office examiner is not a guarantee the patent will not be invalidated by a court, or the patent office, at some point in future. In fact, we will learn later3 that a large proportion of patents, estimated to be around 50%, are invalidated by the courts when litigated. So the grant from the patent office is something of a presumption of validity, not any form of guarantee.

3See the section titled “Why there’s Safety in Numbers for Patents”.

Pending Applications

A patent application is a request pending at a patent office for the grant of a patent for the invention described and claimed by that application. An application consists of a description of the invention (the patent specification), together with official forms and correspondence relating to the application. The process of “negotiating” or “arguing” with a patent office for the grant of a patent, and interaction with a patent office with regard to a patent after its grant, is known as patent prosecution. Do not confuse patent prosecution with patent litigation which relates to legal proceedings for infringement of a patent after it is granted.

The rights associated with a pending application are somewhat speculative, as until the grant is allowed by the patent office examiner, it is not yet clear what the scope of the patent will be (as defined in the claims). It is also unclear as to whether the patent will be granted at all.

Provisional Applications

Under U.S. patent law, a provisional application is a legal document filed in the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) that establishes an early filing date, but does not mature into an issued patent unless the applicant files a regular non-provisional patent application within one year. The date of filing of the provisional patent application can also be used as the foreign priority date for applications filed in countries other than the United States and for an international application covering several countries4. The provisional patent application is only pending for 12 months prior to becoming abandoned and a real patent application must be filed before the 12 month window closes.

Provisional applications are not really necessary, as an inventor can instead file a real patent application. However, a provisional application is often used to document and “lock in” potential patent rights while attempting to obtain sponsors for further development (and for more expensive patent applications). This tactic may permit an inventor to defer major patent application costs until the commercial viability (or futility) of the invention becomes apparent.

4There are different rules for design patents.

Patent Infringement

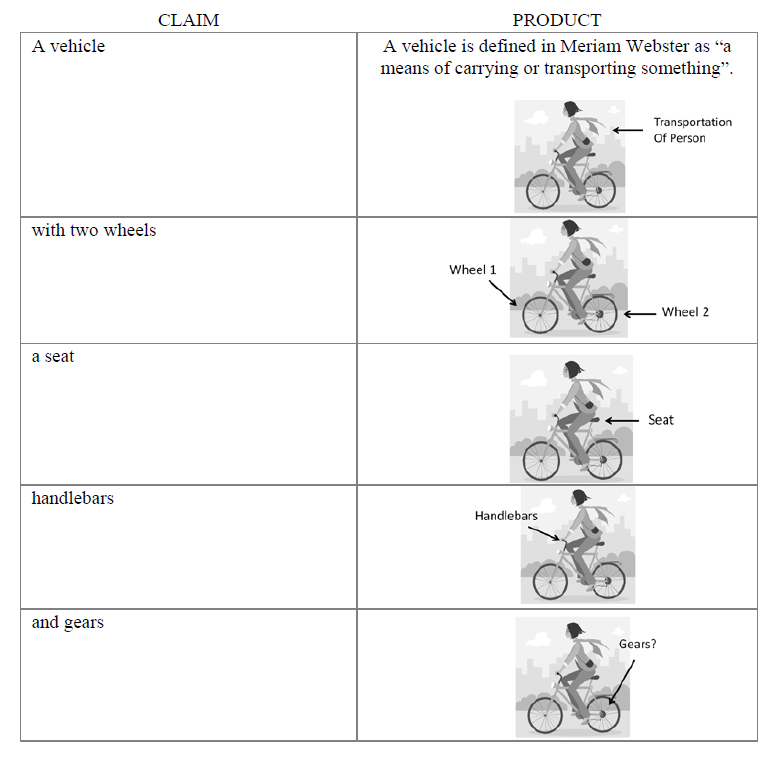

Infringement takes place when each (and every) element of a patent claim is practiced in a product or service used or sold on the market without permission of the patent holder. It’s products that infringe patents, and you will see in the section on Claims Charts (page 69), how evidence of infringement involves mapping the claims of a patent to the features of a product. Before reading further, it’s important to understand that a patent cannot infringe another patent. Products (and services) can infringe patents and it’s the patent claims that determine when infringement takes place.

WHY BUY A PATENT?

There are three primary reasons to buy a patent:

- To assert against an infringer, extract royalties and perhaps an injunction to stop future infringement. Companies facing patent infringement lawsuits often buy patents that are infringed by their opponents in order to file counter-claims.

- To deter attacks from competitors. Another product-seller might think twice about bringing suit against you if you hold patents that they infringe and might be used against them in a counter-claim.

- To file new child applications, and develop a portfolio benefitting from the priority date—the original filing date of the parent.

There are other reasons for companies to buy patents, and some are more valid than others:

- Defendants often acquire patents as part of a lawsuit settlement. The defendant sometimes buys the patents directly, or acquires them via a third party such as a defensive patent aggregator.

- To keep the patent out of the hands of dangerous non-practicing entities (NPE’s) and competitors. If a company is worried it might be infringing the patent, it might take the patents off the market to avoid defending a costly lawsuit later on.

- To qualify for investment or tax incentives available only to patent-holders. In some countries, investors seem to require startups to hold patents, or patent applications before they consider investing. Strangely, these investors don’t always investigate the quality of the patent(s) and many startups find themselves filing patents of questionable value. Some tax authorities offer incentives to companies holding patents—again the quality of the patent doesn’t seem to have any bearing on the tax-saving implications.

- To collect royalties from existing patent licensees. Where a patent is licensed, and royalties are flowing to the patent holder, a financial acquirer may be interested in buying the patents in order to pocket the ongoing revenue streams. This situation is relatively rare.

In a market sector where a product may be comprised of only one or a handful of patented inventions (see Patent-Packed Products and Single-Patent Products, page 33), there may be a compelling reason to buy a patent in order to make and sell products featuring the invention. However, in densely patent-populated products, like smartphones, companies see no compelling need to buy any individual patent in order to build the product. If the product comprises thousands of patented inventions, buying any individual patent is not going change the company’s strategic position with respect to that particular product.

WHY SELL A PATENT?

The vast majority of patent sale transactions involve the buyer paying the seller for the patent, and providing the seller with a license-back. The license back provides the seller with a right to continue practicing the invention by building its own products, without worrying about the buyer coming back and asserting the patent against the seller in an infringement suit. Following a patent sale, the seller usually deposits cash in the bank and continues to market its products unhindered as a result of the license-back.

There are clearly upsides to selling a patent. Unfortunately, many patent holders are unaware that unless they have a war-chest of funds for legal fees, and an army of lawyers (at least a credible patent litigation team), their patent portfolios can be somewhat redundant. Patents represent idle, under-utilized assets for many companies, especially smaller organizations incapable of asserting their portfolios effectively in court. If a small company holds patents it is unable to assert, then sells them to another patent-savvy buyer with a license back, the company can benefit from the buyer asserting the patents against its competitors. The seller’s strategic position in the marketplace can be enhanced by selling patents, as competition can be restricted by the buyer.

Selling can be a win-win scenario for patent holders, but unfortunately patent-holding companies are often unaware of this opportunity as they rely on their patent attorneys for advice and guidance, and many patent attorneys are focused on prosecuting new patents, rather than buying, selling or licensing existing patents.

Common Mistakes Made by Patent Sellers

Patent holders are not always familiar with the patent marketplace and seem to make some very common, and expensive mistakes with their approach to selling:

- Set too high an asking price—when the seller sets the asking price far above the market rate, buyers are reluctant to even consider the patents. The evaluation process for the buyer is expensive and they won’t waste their time looking at the patents if they suspect the seller is not going to be reasonable on price5.

- Present an image of being unreasonable/unrealistic—following from the point above, buyers are scared away by sellers who appear to be erratic, unreasonable or unrealistic in their negotiation style and other aspects of their personalities. Inventors are accustomed to thinking out of the box, but they can be difficult to do business with if they’re too far out of this particular box. Patent buyers have learned to run a mile when they suspect they’re dealing with a mad-cap inventor.

- Fail to accept a reasonable offer—sometimes sellers incorrectly assume an offer from a buyer will remain open indefinitely, and assume there are other buyers in the market prepared to pay a higher price. Very few patents interest buyers6, and the number of buyers interested in a particular patent is usually one or zero. A seller refusing to accept a reasonable offer acts as a signal to the brokers and other buyers indicating the seller is unreasonable. Buyers steer clear of these patents to avoid wasting time and money on patent evaluation when they suspect the seller will not accept a reasonable offer and process will be futile.

- Appoint multiple brokers—one plus one does not make two when it comes to patent brokers. One plus one often makes zero. When there are two or more brokers involved in marketing a patent, none of the brokers are prepared to invest in preparing the sales materials, and the patents are usually not marketed effectively7.

- Fail to gather evidence of infringement—many buyers will only consider patents with claims charts evidencing infringement, so when this is not provided by the seller, the patents are not taken seriously8.

- Assume buyers are motivated to buy the patent in order to build the invention—buyers are generally looking for patents infringed by their competitors, not inventions to build into products9.

- Select patent attorneys unfamiliar with litigation—if the patent attorney writes claims that have not been designed to be asserted against infringers in court, the patent will likely be unsellable at any price. Buyers want patents with claims readily understood by a jury and readily able to be mapped onto products using claims charts10. The most valuable patents are usually written by patent attorneys familiar with patent litigation.

- Send patent numbers directly to buyers—patent holders can upset buyers and even trigger declaratory judgment lawsuits when they send patent numbers to prospective buyers11.

- Fail to read this book—hopefully on reading this book, a patent seller should gain some insights into the patent sale process and have the information necessary to avoid making costly mistakes.

5 For sample pricing see See Data Points from Patent Sale Transactions, page 52.

6See Only One in a Thousand Patents Are Litigated in Court, page 29.

7See The Patent Broker’s Exclusivity, page 99.

8See Claims Charts & Evidence of Use, page 67

9See A Market Driven by Litigation, page 14.

10See Claims Charts & Evidence of Use, page 67.

11See Approaching Potential Buyers with Claims Charts, page 69.

A MARKET DRIVEN BY LITIGATION

Patents have traditionally been considered trophies by some organizations. The research and development teams count patents as evidence of their scientific and engineering prowess and confirm the organization’s industry-leadership position. As trophies, patents are expensive to accumulate and with the growth of patent litigation in many sectors, the true nature of patents as weapons of litigation has taken hold in corporate boardrooms all over the world.

Litigation has grown significantly in recent years. The PCW 2012 Patent Litigation Study12 states:

- “..the annual number of patent actions filed has increased at an overall compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.4% since 1991. We attribute this upswing in part to a 22% increase in the number of filings in 2011 over 2010. The number of patent actions filed reached 4,015 in 2011—the highest number of annual filings ever recorded.

- Meanwhile, the number of patents granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has also grown steadily, increasing at a CAGR of 4.5% since 1991 and increasing by 5% in 2011 to 244,430.”

Many believe the only effective way of monetizing a patent is through litigation. That might be a sweeping statement, but it’s safe to say that patents and litigation go hand in hand. Patents are weapons of litigation, and litigation is the only substantive right that the patent office provides to the inventor.

Money talks and money drives the patent industry as it does with every other industry. Patent values increase, and the number of patent sales increase as the result of growing litigation, and mounting damages awards resulting from the lawsuits. Large, newsworthy damages awards, such as the 2012 $1bn judgment against Samsung, in favor of Apple, grabs the attention of other patent holders and certainly gets noticed by lawyers.

12Source: 2012 Patent Litigation Study. “Litigation continues to rise amid growing awareness of patent value”. PCW (PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP). http://www.pwc.com/en_U.S./us/forensic-services/publications/assets/2012-patent-litigation-study.pdf

Litigation Driven Licensing

Licensing is also connected with litigation. It’s not exactly surprising when you think about it, but companies making and selling products are not often enthusiastic about paying patent royalties. Accused infringers will try to avoid paying royalties and usually write checks only when they’re forced to. This reluctance to pay a patent license royalty is not merely a reflection of bad attitude on the part of management or some disdain of the patent system. Officers and directors of a corporation have a duty to maximize the financial return to their shareholders which generally means minimizing costs and maximizing revenues. Managers and lawyers representing these companies are duty-bound to challenge claims of patent infringement, and are required by their shareholders to resist paying patent royalties unless forced to by a court of law. Many patent holders have found litigation to be the most effective method of monetizing a patent through licensing.

Regardless of how charming or persuasive you may be, if you approach a company, inform them of your patent, accuse them of infringing, and ask them to pay a royalty, you will most likely by met with a surprisingly hostile response along the lines of: “See you in court!”. Even the friendliest of patent sale or licensing discussions are based on the inherent threat of litigation.

Companies don’t usually investigate which patents they might be infringing when marketing a product or service. In patent-packed products, comprising tens or hundreds of thousands of patented inventions, the process of identifying which inventions are infringed would be an enormous task (see The High-Tech Sectors Feature Patent-Packed Products, page 34). If the company does run searches and identifies patents infringed by its products, the company is now infringing knowingly, and willfully13, so is open to punitive triple-damages claims when the infringement case comes to court. As a result, companies routinely adopt policies to avoid exposure to third-party patents.

When a company receives a letter accusing infringement, the company routinely fails to respond to the letter, as this could provide evidence the company was on notice of the patent, and would start the clock ticking on a potential claim of willful infringement. This situations changes though when a lawsuit is filed.

When patents are licensed, this is how the vast majority of patent licensing deals play out:

- The patent holder discovers a company (the infringer) has been practicing the patented invention without a license. They are selling products featuring the patented invention.

- The patent holder contacts the infringer, informs them of the patent, and suggests a license involving a royalty payment.

- The infringer follows its policy of not creating evidence to confirm it is aware of the patent and the infringer deliberately fails to respond.

- The patent holder initiates a lawsuit against the infringer.

- 5. Compelled by lawsuit the infringer is forced to respond.

- The infringer assesses the strength of the legal team it faces in the suit, and the strength of the evidence of infringement. When the case against it looks strong, the infringer comes to the negotiating table and agrees to pay a license fee.

- The infringer pays the patent holder a single payment to cover all past infringement and provides a license for the infringer to continue to use the patented invention in future.

Some of the licenses play out in a slightly different process, as the infringer triggers the lawsuit in order to gain an advantage by selecting the jurisdiction, the court where the case will be heard:

- The patent holder discovers a company (the infringer) has been practicing the patented invention without a license. They are selling products featuring the patented invention.

- The patent holder contacts the infringer, informs them of the patent, and suggests a license royalty arrangement.

- Infringer (not the patent holder) brings a lawsuit for declaratory judgment, asking the court to declare the company is NOT infringing.

- The patent holder is forced to hire a legal team and file a counter claim accusing infringement, otherwise the patent holder forever loses the right to bring a claim of infringement against this opponent.

- The infringer assesses the strength of the legal team it faces in the suit, and the strength of the evidence of infringement. When the case against it looks strong, the infringer comes to the negotiating table and agrees to pay a license fee.

- The infringer pays the patent holder a single payment to cover all past infringement and provides a license for the infringer to continue to use the patented invention in future.

Due to the policies adopted by companies, afraid of creating evidence they are on notice of a patent as a result of triple damages fears, patent holders often find the only effective method of triggering a response from a potential licensee, and opening the licensing discussions is to initiate a lawsuit. To a great extent, patent licensing as well as patent trading activities are driven by litigation.

1335 U.S.C § 284 – Damages “..the court may increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed.”

FEW COMMERCIALIZATION OPTIONS FOR INVENTORS

Innovative new ideas often come from small independent inventors, but frequently need the resources of large corporations to bring them to market. Successful commercialization of new products requires a combination of finance, management, sales, marketing capabilities, perseverance and not an insignificant amount of luck.

When managing products and marketing at Apple, I had the opportunity to see how the process worked for large multinationals. After I left Apple and formed a number of small startup companies, I saw a different perspective. Customers are reluctant to buy from startups, as it is common knowledge that startups fail at an alarming rate and customers want suppliers they can rely on being around for years to come. The failure rate of startups is hardly surprising considering they lack the credibility, and the muscle to out-compete large, incumbent competitors. A Harvard University paper14 studying venture capital backed startups showed that 18% of first time entrepreneurs succeed and 82% fail. The odds are slightly improved for previously successful entrepreneurs where 30% succeed and 70% of their startups fail. Bearing in mind the companies studied here were all backed by millions of dollars in venture capital financing, the failure rates of all startups (including those unable to raise venture capital funding) is even higher than 82%, and the odds are stacked against achieving successful product commercialization via a startup venture.

After forming and running more than ten startups, I wrote a book called Zero-To-IPO15 where I analyzed the startup process, writing a roadmap and travel guide for entrepreneurs on the high-tech startup journey. I found establishing effective channels to market was the largest obstacle to startups. It might cost a few million dollars, and take a couple of years to convert an invention into a a hot new product, but creating the sales, marketing and distribution channels necessary to bring many high-tech products to market can take decades and cost hundreds of millions or billions of dollars.

Sectors like consumer electronics, semiconductors, computers, software, medical devices, the Internet, media and even video gaming are dominated by huge multi-billion dollar, multi-national corporations today. Even startups with innovative ideas and hot products struggle to penetrate these sectors and compete with the established market leaders. Some startups, like Facebook, obviously do manage to make it through the early stages and hit the news, but those with experience of venture capital are painfully aware that success is highly elusive in Silicon Valley. The chances of commercializing a new invention through a startup venture are extremely slim, even if you are able to raise venture capital.

If the startup route is too risky for an inventor, perhaps they should consider selling their invention to a product company? After completing my Zero-to-IPO book, I formed Tynax in 2003 as a technology trading exchange to help entrepreneurs sell their products and inventions to large corporations looking for new products and revenue streams. The online technology trading exchange concept seemed like a perfect venue for large corporations to shop for new technologies. However, we found large corporations reluctant to buy technologies from outside. If there’s a technology they like, rather than buy it, they are more inclined to just copy it. Multinationals pay lip service to the whole concept of “Open Innovation”, and are reluctant to write checks to buy technology they can build themselves. Patent law is the only barrier to such copying, so we found the buyers were only really interested in patents, and then only in patents that could be asserted against them or their competitors in court. Responding to the market, the Tynax technology trading exchange became the Tynax patent trading exchange comprising tens of thousands of patents for sale.

Startups often fail and large corporate buyers have little interest in acquiring technology, and they buy patents as weapons of litigation. The options open to inventors for product commercialization are somewhat restricted, and we are returned to the reality that the patent market is driven by litigation, not product development.

14Gompers, Paul A., Kovner, Anna, Lerner, Josh and Scharfstein, David S., Skill vs. Luck in Entrepreneurship and Venture Capital: Evidence from Serial Entrepreneurs (July 2006). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=933932 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.933932

15Available as free ebook at www.zero-to-ipo.com.

THE PATENT MARKETPLACE

Patent sale transactions have been taking place for centuries, but only recently hit the mainstream news. The patent wars in the smartphone sector have been well covered by the news media, especially the activities of large players like Apple, Samsung and Google. Since Apple and its allies paid $4.5bn for patents from Nortel, many commentators have described the marketplace as a “patent bubble”16. Following the Nortel transaction in 2011, there have been a number of other high-profile patent sales involving Microsoft, AOL, Facebook, Google, Motorola Mobility, Kodak, Intel and IBM. Some estimate the value of patent sale transactions to have grown ten-fold since 2010.

Unlike other industries, like for example the legal profession where the majority of firms operate under a consistent business model (hourly billing or contingency fee), the patent trading industry is extremely disperse with a wide array of players, and an impressive array of business models. It seems almost every player in the industry has its own unique strategy for making a profit.

Of course we have the large operating companies like Apple, Google, Samsung, Microsoft and Intel who sell patent-packed products such as smartphones, semiconductor chips and electronics. Other large corporations like Abbot Labs, Johnson & Johnson sell products featuring a relatively small number of patents, but still accumulate large patent portfolios.

There are non-practicing entities (“NPE’s”), sometimes referred to as “patent trolls” who don’t sell their own products, but focus on patent assertion and licensing. NPE’s prey on operating companies with deep pockets—companies like Apple, Google, Samsung, Microsoft and Intel. As a counter-balance to the NPE’s, we now have defensive patent aggregators who acquire patents to protect their operating company members from excessive litigation.

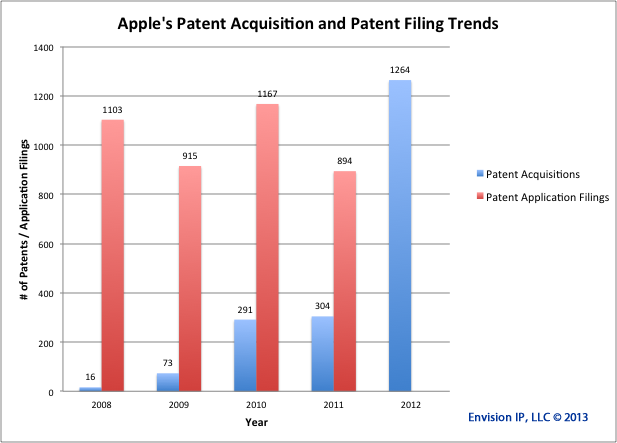

Patent acquisitions have become a major source of patents for some large corporations today. Envision IP analyzed Apple’s patent acquisitions, and as you can see from the chart, Envision IP reports17: “Apple’s patent acquisitions have increased year-over-year since 2008, while its U.S. patent application filing has been staggered… Patent applications are published 18 months from filing, so we do not have access to 2012 and 2013 filing data.”

Further characteristics of the patent marketplace:

- Consortia—companies don’t always act alone, and buyers have formed consortia to acquire expensive portfolios, as we saw when Sony, Microsoft and RIM joined with Apple to acquire the Nortel patents, forming a new corporate vehicle called Rockstar.

- Sovereign equity funds—government sponsored funds have been formed in countries like Korea and Taiwan to acquire patents, build patent pools and protect their own companies from expensive patent litigation.

- Intermediaries—there are brokers and agents representing patent sellers. These intermediaries promote and market patents for their clients, usually earning a commission from patent sale transactions. There are brokers and agents representing buyers who scout for quality patents and shield their buying clients from potentially dangerous patent holders.

- Organizations and individuals large & small—the patent sellers comprise individuals, emerging startups, failed startups, large corporations, universities, R&D labs, and a wide range of organizations.

- Attorneys—lawyers are found in all areas of this business, acting as brokers, negotiating patent sale transactions for their clients, undertaking evaluation of patents, negotiating licenses and forcing everyone in the industry to sign NDA’s.

This is a vibrant, fast-moving industry that’s somewhat unpredictable. When we look back in future decades, we will probably describe the industry today as immature and experimental.

16See “Patent hunting is latest game on tech bubble circuit”, Richard Waters for Financial Times, July 27, 2011. “You could call it the Great Patent Bubble of 2011.” http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/16025f76-b868-11e0-b62b-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2INjuGKC6

17Source: Envision IP. http://envisionip.com/blog/2013/02/22/506-apple-patent-acquisitions-fueled-by-product-development/

PATENT LITIGATION ATTORNEYS

While other practices of law are in decline, patent litigation is booming. As patent litigation has been growing over recent years, and the jury awards can be quite lucrative, many litigators have turned their attention to patents and this area of law is bucking the trend. Along with the traditional, there are also somewhat untraditional business models adopted by lawyers involved in the patent trade.

Hourly Rate Firms

Patent litigation attorneys usually have rate card with an hourly rate for their services, often in the range of $300-$900 per hour. Where lawyers representing the plaintiff (patent holder bringing the lawsuit) can operate on a contingent (revenue sharing), the defense lawyers representing the accused infringer operate on an hourly-rate basis. The costs associated with patent litigation are monitored and reported by AIPLA, the American Intellectual Property Law Association. The median costs of a patent infringement in 2011, were reported to be $5m when more than $25m was at risk and $2.5m when less than $25m was at risk (but more than $1m was at risk)18. AIPLA reports “While these figures represent the median cost, the actual cost could be substantially higher. As an example, the estimated costs of a patent infringement suit ranged from $2,500,000, to $7,500,000.” The bulk of these costs are represented by hourly-rate legal fees charged by litigation attorneys.

18AIPLA, 2011 Report of the Economic Survey. See http://www.aipla.org/advocacy/executive/Documents/AIPLA%20Comments%20to%20IPEC%20on%20Joint%20Strategic%20Plan%20on%20IP%20Enforcement%20-%208.10.12.pdf

Contingent-Fee Firms

The cost of bringing a patent litigation suit is measured in millions of dollars and many patent holders are reluctant, or unable, to engage attorneys on an hourly-rate basis. For patent holders, a contingent no-win—no-fee relationship with a team of litigators can be appealing. For the litigators it can be quite lucrative, if they win of course, and the contingent fee approach has gathered some momentum.

This is how it usually works: the law firm swallows the legal fees and in exchange takes something in the region of 33-38% of the award when it wins the case. If the case then goes to appeal, the fees often increase to 50%. Half goes to the lawyers and half goes to the patent holding client. However, there are some quirks to consider when examining this model:

- The lawyers usually bill the client for their hours. Although the client is not required to pay the bills, each month the client receives a bill (usually for several hundred thousand dollars) representing the hours worked by the lawyers and their assistants.

- The accumulated legal fees are deducted before the profits are shared with the client. So, let’s say the case goes to appeal, the lawyers earn 50% of the proceeds, and the accumulated fees to the date of trial are $3m, then the lawyers take their $3m in accumulated legal fees and share the remaining funds with the client on the 50:50 arrangement. The legal fees are paid in full before the remaining “profits” are shared with the client.

- Lawyers usually require the client to pay some of the costs. If the lawyer is exposed to the extent of several million dollars in legal fees, the lawyer is funding the suit, and is inclined to take a settlement offer seriously when offered by the opposing side. The client, though gets to decide whether to accept the offer or not. If the client is not paying any of the legal fees, has no “skin in the game”, the client may readily decide to reject a settlement offer and continue with the litigation (at the expense of the lawyers). As a result, contingent lawyers like to see the client bearing some of the costs, so their interests are aligned when it comes to discussing a settlement. A client is more likely to take the settlement offer if the alternative involves the client paying additional legal fees.

Although they may be required to stump up a small percentage of the ongoing legal costs, this business model may appeal to a large number of patent holders. They don’t have much to lose, and potentially a great deal to win. However, contingent law firms are very picky about the cases they take on and this is not an option for the vast majority of patentees.

Contingent lawyers have to make a series of financial calculations before taking on a case. There’s the multi-million dollar cost in legal fees, then there’s the time consideration, as the average time-to-trial takes 2.5 years19. If the case goes to appeal, this timeframe is extended. Factor into this the reality that around half of all patents litigated are found to be invalid in court (see Why there’s Safety in Numbers for Patents, page 28) and you have an interesting spreadsheet with millions of dollars in costs, a significant risk of failure, and a multi-year commitment. When you run these numbers, to justify taking on a patent infringement case, the contingent law firm needs a potential award from the court of at least $50m. A $50m award for infringement at a 1% royalty rate requires $5bn of infringed product sales by the defendant(s).

What does all this mean for the patent holders? Well, unless you have at least $2.5m to invest in legal fees, or your patent is infringed to the tune of $5bn (with a “b”), you will likely be unable to hire a lawyer to represent you even if your patent is infringed.

What does this mean for contingent lawyers? If you’re a litigator, you have to be very picky about the cases you take on a contingent basis. You need to fully evaluate the patent and forecast the lawsuit before committing to take on a contingent client.

This void in availability of litigation attorneys for patentees provides a nice segue to our discussion on the emergence of a new breed of law firm called non-practicing entities.

192012 Patent Litigation Study, PWC.

NON-PRACTICING ENTITIES (“NPE’S”)

When a company sues a competitor for patent infringement, it is reasonable to expect the competitor to file a counter-suit. A counter claim of patent infringement is an effective measure, as attack is thought to be one of the best forms of defense. However, any accusation of patent infringement (in a claim by the plaintiff, or a counter-claim by the defendant) requires evidence that the patented invention appears in the product or services being offered by the opposing party. So it’s hardly surprising to find that patent infringement suits by competitors against competitors often involve counter-claims.

Now what if the patent holder filing the suit did not make or sell any products or services at all? It would be essentially immune from counter-claims when it asserts patents against an accused infringer. This immunity to counter-claims has led many lawyers and organizations to focus on asserting patents, and to avoid “practicing the inventions” themselves. They do not practice any patented inventions, so they are referred to as “non-practicing entities”, and these entities have grown in number and in scale over the last few years. If you prefer, you can think of NPE’s as “non-product entities” as the lack of products is their key differentiating factor.

As long as patents represent legal rights to exclude others from practicing patented inventions, there will always be lawyers bringing cases against infringers. Patent litigation lawyers will adopt a variety of business models, some of which will involve accumulating patents in business entities that do not practice the inventions, but focus on legal matters and litigation. So, non-practicing entities are here to stay, and the defendants facing these entities in court will likely find derogatory terms to describe their opponents, and will likely continue to request changes in the patent laws to curtail their capabilities.

NPE as Evil “Patent Troll”

Non-practicing entities have been characterized, usually by corporations they face as opponents in court, as patent trolls20. Corporate lawyers often argue that NPE’s don’t produce anything of value but merely tax the hard work and innovation of successful product manufacturers. Companies like Google and Cisco have been outspoken critics of the U.S. legal system for allowing patent trolls to “stifle innovation” and have called on the U.S. Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission to take action to restrict the capabilities of NPE’s21.

20The term “patent troll” was used as early as 1993 to describe companies that file aggressive patent lawsuits. The Patent Troll was originally depicted in “The Patents Video” which was released in 1994 and sold to corporations, universities and governmental entities. The metaphor was popularized in 2001 by Peter Detkin, former assistant general counsel of Intel.

21Regulators Take a Look at Patent Firms’ Impact, Wall Street Journal November 18th, 2012

22eBay Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C., 547 U.S. 388 (2006)

Different Rule of Law for NPE’s

Following a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 2006 in a case involving eBay22, NPE’s have been unable to win injunctions against infringers and have been forced to focus their efforts on winning damages. Where an operating company participating in the market by practicing inventions, making and/or selling products is able to win an injunction, an NPE is not. So we have a bifurcation appearing in the legal system where one set of rules is applied to NPE’s and another is applied to operating companies. As a result, some NPE’s are buying whole companies, instead of merely the company’s patents, in order to claim to be participants in the marketplace, and in order to qualify for injunctive relief against infringers.

As a result of a finding of patent infringement, before this eBay case, the court would almost routinely award an injunction to prevent future infringement as well as an award of damages to compensate for past infringement. Asking a large corporation to write a check for damages is painful but not as disruptive as asking the company to stop the production lines, and remove products from the shelves, so the threat posed by NPE’s was somewhat diffused by the eBay ruling. However, NPE’s are still able to request damages for royalties on infringed patents and the number of NPE’s has continued to grow following the eBay ruling.

NPE as “White Knight” for the Small Inventor

Large corporations use muscle to deter patent assertion by small patent holders. The message received by small patent holders from large corporations can often be characterized along the following lines: “We’re not going to pay any royalties unless you sue us. Unless you have an army of lawyers and a war chest of funds to finance a lawsuit, we’re not going to take you seriously at all.”

The startup failure rate is extremely high. Indeed the vast majority of startups fail23. Failure is partly due to the power, muscle and monopolistic or oligopolistic practices of the large, incumbent market leaders. Many startups succeed in creating new technologies, designing innovative new products and developing portfolios of important patents. However, these startups then fail to raise the finance necessary to build a global brand, establish sales and marketing channels and effectively compete with the huge multi-billion dollar incumbent corporations. Running out of funds, the startups lose their staff, lose their credibility in the marketplace, and often the only significant assets they are left with are their patents.

Failed startups with patents can approach large corporations infringing the patents, but they are routinely ignored until they threaten legal action. Then the inventors find themselves facing tough corporate lawyers who refuse to consider paying any license fees unless they are forced to. Corporations will usually only open up their check books when threatened by litigation-quality patents, and credible lawyers with millions of dollars available to pursue legal action in the courts. So, failed startups and other small inventors rely on contingent lawyers or specialist firms with deep pockets when it comes to asserting their patent rights against large corporate infringers. Many non-practicing entities represent the little guy, and argue their role is critical to defending small inventors and encouraging innovation. Large corporations may see NPE’s attacking them as evil patent trolls, but for small inventors, the NPE is often viewed as a white night, defending the rights of the weak against the power of the wealthy. Through the eyes of a product manufacturer, an NPE might appear as a worthless troll, and through the eyes of a small inventor, the NPE appears as a valuable white knight.

23 If failure means liquidating all assets, with investors losing most or all the money they put into the company, then the failure rate for start-ups is 30 to 40 percent. If failure refers to failing to see the projected return on investment, then the failure rate is 70 to 80 percent. If failure is defined as declaring a projection and then falling short of meeting it, then the failure rate is a whopping 90 to 95 percent. Source: Harvard Business School. http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/6591.html

Aggression by Proxy

Large corporations seem to have a love/hate relationship with NPE’s and often feed them with patents to assert against their competitors. The Wall Street Journal24 reports: “Nokia and Sony Corp. of America, for example, have assigned some of their patents to an entity called MobileMedia Ideas LLC, which has sued Apple Inc. for patent infringement in a Delaware federal court. In another case, Google Inc. lodged an antitrust complaint with European regulators this year against Nokia and Microsoft. The search giant alleged that Nokia and Microsoft were using a patent entity as a proxy to hurt the prospects of Google’s Android mobile-phone software.” By selling or assigning patents to an NPE, and retaining a license back, an operating company is able to have the patents asserted against competitors and escape being characterized as the aggressor. NPE’s are specialist patent litigators that are often fed patents by corporations, launch lawsuits and undertake aggression by proxy. There’s little wonder NPE’s claim they are called on to carry out the “dirty work” in the patent industry.

Corporations that do undertake this form of aggression by proxy, can face repercussions. For example, in February 2013, Google launched a lawsuit against British Telecom. It’s unusual for Google to initiate action, but this was how Google justified the suit:“We have always seen litigation as a last resort, and we work hard to avoid lawsuits. But BT has brought several meritless patent claims against Google and our customers — and they’ve also been arming patent trolls. When faced with these kind of actions, we will defend ourselves.”25 BT’s sale of patents to NPE’s who subsequently sued Google contributed to the initiation of the lawsuit by Google, and corporations do have to take this into consideration when “arming patent trolls” and engaging in aggression by proxy.

24Wall Street Journal. Law Journal. November 18, 2012, Regulators Take Look at Patent Firms’ Impact.

25http://www.zdnet.com/uk/google-slugs-bt-with-four-patent-countersuit-after-telco-armed-trolls-7000011310/

WHICH PATENTS SELL?

When you look at the patent transactions that take place in the marketplace, you see the following characteristics:

- The sales comprise families of issued patents (rather than individual patents, or applications).

- The patents are being infringed.

- The infringement involves substantial sales volumes.

- The infringement is evident (can readily be observed).

- Transactions are taking place in market sectors where patent wars are raging.

If all these five characteristics are found in patent sales, how many of the five should a patent holder have if he/she hopes to be successful in finding a buyer and selling a patent portfolio at an acceptable price? As a general rule, the answer is “all five”. If you take a random sample of patent sale transactions, perhaps those disclosed in the news reports, and check them against these 5 criteria, chances are that you will find all five criteria were met.

SELLING PENDING APPLICATIONS

As a general rule, there are no buyers for pending applications (and provisional patents) unless they are sold as part of the family alongside issued U.S. patents. Until the claims have been allowed by the patent examiners, the scope of the patent is undetermined, and the value of the patent is too speculative for a buyer to acquire. There’s speculation on behalf of the buyer as to whether the patent will be granted, speculation as to whether any useful claims will be allowed, and speculation as to how long the process will take. Some patent applications take years to get approved by the patent examiners. My own patent, where I was an inventor, took ten years to work through the process.

As a result of its speculative nature, the chance of finding a buyer for a single pending application is negligible. The chance of finding a buyer for a handful of applications is increased to “not impossible”, but I have seen large numbers of applications (like 10-20 or more) that sell on the patent market when offered as a bundle. With a number of applications in the same family and technical field, the odds of having some useful claims allowed increases and some value is attached to the portfolio, even before there are any issued (granted) patents in the family.

A pending application can be of more interest to a buyer when the window of opportunity to modify the claims language, and other important features of the application, is open and the buyer is able to customize the patent and draft up the precise wording forming the claims. Once the window of opportunity to modify the claims has closed, many potential buyers will lose interest in the application. This is particularly true when the inventor wrote the application himself/herself and failed to bring in an expert patent attorney to draw up the claims. I have seen many situations where the buyer is unimpressed by the patent-writing skills of the seller, and is only interested in acquiring the application if the window remains open to re-draft the language.

Pending applications do have the effect of bumping up the value of the granted parent patents. When a patent is sold, the value is boosted by perhaps 20-30 percent when accompanied by a family of open continuation applications. This enables the patent buyer to develop their own new patents and portfolios using the pending applications as foundational building blocks.

SELLING INTERNATIONAL (NON-U.S. PATENTS)

Patent buyers are interested in acquiring patents that can be licensed to infringers, or at least asserted against infringers, and many believe the best place to assert and license patents is the United States. There are two reasons for the U.S. being the primary market for patent licensing and litigation. Firstly, the U.S. economy is the largest in the world, and infringed products usually ship in higher volume in the U.S. than they do in other countries. The second reason is the legal framework for patent litigation, and the U.S. Federal court is well known and well trusted by patent holders.

Litigation drives the patent trade, and litigation is taking place in countries other than the U.S., so you would think that patent trading in those countries was also very vibrant. However, the financial damages awarded outside the U.S., even in large markets like China, are dwarfed by those in the United States.

China has a vibrant and growing patent market. Tnd number of patents filed, and the number of patent litigation lawsuits in China now outstrips the U.S. However, where the lawsuits in the U.S. usually demand damages measured in tens of millions of dollars, the suits in China often involve demands for tens of thousands of dollars. The damages awards outside the U.S. are so small that patent assertion is considered hardly worthwhile. As a result, the vast majority of patents traded are U.S. issued patents, or U.S. patents sold together with international counterparts.

This is not to say that the patent buyers are all U.S. companies and trading only takes place in the U.S. Many of the world’s largest companies are headquartered in countries such as Japan, China, Taiwan, Germany, and Korea and these multinationals are active players in the patent trade—as litigants, buyers, and sellers. The vast majority of the assets they are trading though are patents issued by the U.S. patent office. International patents generally are bundled with the U.S. asset and sold alongside.

WHY THERE’S SAFETY IN NUMBERS FOR PATENTS

The patent examiners do not have unlimited time and budget to research a patent application, and often grant patents that are later invalidated in court, or by the patent office itself.

When a patent is litigated against an accused infringer, the accused infringer has several defenses to deploy. Some of these defenses are aimed at invalidating the patent. In the U.S., one of the most common reasons for invalidating a patent is “prior art” where evidence is discovered to show the inventor named on the patent was not the first person to come up with this invention (see Prior Art, page 83). The rules are changing somewhat as the U.S. comes into line with the rest of the world and issues patents to inventors on the basis they were the first to file, not the first to invent. The defense of prior art may not be so potent at invalidating patents during the litigation process as a result of this new legislation, but there are other defenses that can be used, such as best mode—where the accused infringer shows that the inventor of the patent failed to teach in the patent the best mode for deploying the invention.

Whether it’s prior art, best mode or some other defense, many patents that appear to be valid when they enter the litigation process are declared invalid by the court. When declared invalid, the patent is essentially rendered null and void, worthless as a weapon of litigation, and worthless for pretty much anything else.

| Number of Patents | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Chance of All Being Invalidated | 50% | 25% | 12.5% | 6.25% | 3.12% |

“Roughly half the patents that are used in lawsuits are invalidated by the court following a challenge by the accused infringer” 26 . As a result of their fragile nature, patents have been likened to “Lottery Tickets”27 and buyers are taking a risk when acquiring single patents or small portfolios. “When a patent holder asserts its patent against an alleged infringer, the patent holder is rolling the dice. If the patent is found invalid, the property right will have evaporated.”28 If you apply mathematics, on the basis that half patents are invalidated in litigation, then the chance of one patent being invalidated (and rendered worthless) is 50%, with two patents, the chance reduces down to 25%, a portfolio of three patents has a 12.5% chance of all three patents being invalidated, and a portfolio of four patents the odds come down to 6.25%. So, if you’re a patent buyer and you want to make sure the patents you purchase have at least a nine out of ten chance of standing up to the rigors of litigation, then you should always look to buy patents in families of four (issued) patents or more. This is not to say a portfolio of two or three issued patents is not sellable, but the value is certainly affected and smaller portfolios struggle to attract top dollar prices.

26“The risk that a patent will be declared invalid is substantial. Roughly half of all litigated patents are found to be invalid, including some of great commercial significance.” Probablistic Patents, Mark A. Lemley and Carl Shapiro, Journal of Economic Perspectives–Volume 19, Number 2—Spring 2005—Pages 75-98

27Probablistic Patents, Lemley & Shapiro, 2005.

28Probablistic Patents, Lemley & Shapiro, 2005.

ONLY ONE IN A THOUSAND PATENTS ARE LITIGATED IN COURT

Considering the only purpose of a patent is to provide the right to have a court exclude infringement via litigation, the remarkable number unearthed by Lemley and Shapiro in their Probablistic Patents paper in 2005, is “0.1%”. The researchers found: “Most issued patents turn out to have little or no commercial significance, which is one reason that only 1.5 percent of patents are ever litigated, and only 0.1 percent of patents are ever litigated to trial.” As this is critical to understand the nature of the patent trade, I will repeat the number: only one in a thousand patents is ever litigated to trial.

Those of us in the industry know that a very small percentage of patents are ever featured in a lawsuit, that most lawsuits are settled before trial, so the numbers feel somewhat correct. But this does have some serious implications for the patent trade.

If only 1.5% of the patents are ever used in litigation, why are the remaining 98.5% filed at all? There are several reasons for this:

- Many inventions are never commercialized. It’s not necessary for an invention to be commercialized before it’s allowed by the patent examiner and a large proportion of patented inventions are simply bets on a future technology. The technology heads in another direction and these dead-end inventions are never put into practice.

- Some patent attorneys are opportunistic and make a living charging fees to clients for filing patents they will never be able to use. If the client asks for a patent, many a patent attorney is likely to deliver a patent, and a series of invoices, often with little regard to quality.

- Many corporations and organizations are cutting budgets and forcing patent attorneys to work on a low price-per-patent basis. The focus is on price and quantity, not quality. Patent attorneys in these cost-squeezed production-line situations are not inclined to produce top quality patents.

- Some patent attorneys simply don’t know how to write claims that can be asserted in court. Writing claims to be allowed by an examiner is not quite the same as writing claims that will impress a jury and stand up in court.

- Many inventors who file their own patents don’t know how to construct patents of litigation quality. There’s a correlation between quality patents and high-priced patent attorneys. Unfortunately, those “How to File your Own Patent” books don’t teach inventors how to file patents that will stand up to the rigors of litigation.

- Many corporations and R&D organizations are blindly filing patents as trophies to evidence their technical prowess. To customers and uninformed observers, a large patent portfolio might appear impressive and imply the organization has a strong technical capability. However, to patent industry insiders, many of these portfolios make no sense at all—as so many of the patents are too weak to represent any practical value. Hundreds of thousands of worthless patents are being churned out each year by R&D labs, large corporations, universities and other organizations intent on gathering trophies and plaques for their walls.

The percentage of quality patents is surprisingly small, and it seems to be falling over time. The Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2011, published by the OECD29, finds that patent quality has declined by an average of around 20 per cent between the 1990s and 2000s, a pattern seen in nearly all countries studied. A focus on quantity over quality seems to be a theme as the patent race heats up.

If you follow the logic that buyers only want to acquire patents they are able to use (in court), that a patent of litigation quality will be litigated sooner or later, and only 1.5% of the patents are ever litigated, then you reach the conclusion that only 1.5% of patents are sellable. This again might seem like a small percentage, but it does reflect what we see in the patent marketplace.

Lemley and Shapiro state: “Many patents are virtually worthless, either because they cover technology that is not commercially important, because they are impossible to enforce effectively, or because they are very unlikely to hold up if litigated and thus cannot be asserted effectively. A small number of patents are of enormous economic significance… The distribution of value of patents appears to be highly skewed, with the top 1 percent of patents more than a thousand times as valuable as the median patent.”30

Patent holders sometimes see the huge value attached to the litigation-quality patents appearing in the news stories and assume this means their own patents are of similar value. Patent attorneys don’t present this bad news to their clients and it’s often left to the patent broker to explain to these proud inventors that their particular patent is not one in a thousand, not one in a hundred, not suitable for litigation, and is unsellable at any price. Patent brokers often have the unpleasant task of telling inventors their baby is ugly. The task is made more difficult as the result of online patent valuation services tha convince patent holders their patents are highly valuable when they’re not.

Searching through the millions of patents in existence to find the small percentage that could be asserted in court represents a significant burden and explains a great deal about the patent trade. It would be difficult to find another marketplace with such thin trading. Thin trading leads to frustration on the part of unsuccessful sellers, their brokers, and results in relatively high transaction costs for everyone involved.

Note: this is not primarily a book about mathematics, statistics or probability and I realize these numbers are somewhat open to discussion. However, the point is that a very small percentage of patents are of litigation quality, a similarly small percentage of patents are of interest to buyers and the vast majority of patents are unsellable at any price.

29The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) http://www.oecd.org/innovation/innovationinsciencetechnologyandindustry/oecdsciencetechnologyandindustryscoreboard2011innovationandgrowthinknowledgeeconomies.htm

30Allison, Lemley, Moore and Trunkey, 2004; Pakes, 1986; Schanker-man and Pakes, 1986; Lanjouw and Schankerman, 1999

WHERE TO FIND PATENTS TO BUY

As this industry is cloaked in secrecy, finding patents that might be available for sale is not always a straightforward activity. For example, if you search eBay with the word “patent” you’re presented with shoes and handbags for sale. There are a small number of patents listed for sale on eBay, but serious sellers do not post their patent numbers on a public forum like eBay. Imagine if a patent were asserted against an infringer in court, the patent holder was asking for damages of, say $200m, and the defendant disclosed evidence to the jury that the patent in question had been offered for sale on eBay for $100,000. The case for the patent holder could be seriously weakened, and this is one of the reasons why patent sales often take place under a shroud of secrecy.

So where do you go if you’re looking to acquire patents?

- Patent brokers—a large proportion of patents for sale are offered via patent brokers. The number of patent brokers worldwide is likely in the low 3 figures (I’ve identified just over 200) but many of these brokers are small, offering only a handful of portfolios each year. As arms dealers to the patent trade, patent brokers often operate under the radar, and some of the most effective operators, the agents selling the largest numbers of patents are very secretive and difficult to find—unless you’re an active patent buyer. If you’re an active patent buyer, chances are the most effective brokers will find you sooner or later.

- Sellers directly—it’s sometimes possible to find patent holders prepared to sell their patents. For example, Hewlett Packard runs an active patent sale program, and many buyers approach HP directly when searching for patents for sale. Other than HP, IBM, AT&T and a few others, it’s not easy to find organizations prepared to sell their patents. Calling an organization to inquire about selling patents usually results in the call being diverted to a patent attorney who has strict instructions to keep the patent strategy confidential.

- Live auctions—over recent years, ICAP has run a series of public patent auctions. As an effective auction requires two or more bidders competing for the same lot at the same time, and this rarely happens in the patent business, many lots have remained unsold at the conclusion of the auction events31.

- Online patent exchanges—I was surprised to find that there was no online exchange for patents when I first researched this market in 2002. Some players had emerged but died in the dot com crash, and I formed a patent exchange called Tynax.com to fill the void. Tynax now has hundreds of thousands of patents for sale, but the patent numbers are not published online and the Tynax exchanged has been designed to enable brokers, buyers and sellers to transact in a confidential, discrete process.

- USPTO search—as the USPTO.gov website publishes information on every patent ever granted in the United States, some of which are available for sale, the USPTO database is a place to find patents to acquire. The problem is finding the patents that might be available for sale from millions of published patents is not a simple task.

Of course, the challenge is not just finding patents that might be for sale, but finding patents of litigation quality that are infringed by the buyer’s opponents. This is somewhat like finding the needle32 in the haystack, and unfortunately it will never be easy. (See Identifying Which Patents to Buy—The Evaluation, page 73).

31 http://gametimeip.com/2010/11/26/disappointing-results-at-icap-ocean-tomo-auction/ For details of auction results see ICAP Patent Auctions, page 55.

32Patents are weapons, hence the use of “daggers” in the title of the book. Consider a needle a form of dagger. A needle could be used as a weapon, especially against tiny opponents.

PATENT-PACKED PRODUCTS AND SINGLE-PATENT PRODUCTS

The patent office examiners specialize in certain technology types, focusing on certain patent classes, and some desks in the patent office have larger piles of incoming applications than others. Certain technology sectors, such as consumer electronics, attract large numbers of inventors and are densely filled with patented inventions—often referred to as “patent thickets”33. Other sectors see relatively little activity. Important distinctions in patent strategy are driven by the number of patented inventions found in different products.

The patent strategy for a product containing only one, or a few, patented inventions is very different from the strategy you would adopt if your product contained thousands of patented inventions. Looking out at your competitors, your combat strategy is different when facing an opponent holding thousands of patents than it is when facing an opponent with one or a handful of patents. If you’re selling a TV comprising thousands of patented inventions, your patent strategy is very different from the strategy you would adopt if you were selling a paper clip that contained only one or two patented inventions.

| SINGLE-PATENT PRODUCTS | PATENT-PACKED PRODUCTS | |

| Portfolio Size: | Small & Targeted | Large Stockpile |

| Portfolio Focus: | “Our” Products | Competitor’s Products |

| Freedom to Operate Search: | Yes | No |

| Combat Style: | Single-Weapon Hand-to-Hand | Large Scale Arms Race |

| Potential Backlash from Aggression: | Manageable | Unmanageable: “MAD: Mutually Assured Destruction” |

33Shapiro, Carl (2001). “Navigating the Patent Thicket: Cross Licenses, Patent Pools, and Standard-Setting”. In Jaffe, Adam B.; et al.. Innovation Policy and the Economy. I. Cambridge: MIT Press. pp. 119–150. ISBN 0-262-60041-2.

The High-Tech Sectors Feature Patent-Packed Products

The electronics sectors, software, Internet and other high-tech products are densely populated with patents. It is estimated that the number of patents impacting smartphones reaches more than 250,00034. “Roughly 40,000 software patents are issued every year.”35 As there are so many patented software inventions, it is virtually impossible for any software developer to create a product or a piece of code that does not infringe patents held by other inventors. Checking for “freedom to operate” to find fields of software where a software developer can operate free of any existing patents would be unreasonably difficult, even for the largest software developer. A recent study calculates that “..it would take roughly 2,000,000 patent attorneys working full-time to compare every software-producing firm’s products with every software patent issued in a given year.”36

In these densely populated sectors, the strategy adopted by large corporations involves stockpiling weapons and holding sufficient to deter attacks from competitors. Like the arms race in the cold war between the U.S. and Russia, each side accumulates sufficient weapons so the other side is deterred from launching an attack in fear the resulting war will result in mutually assured destruction (it would be “MAD”).

The patent strategies in these patent-packed products are outward looking. Companies look at the products being produced and sold by potential opponents and find patents these organizations might be infringing. This strategy, however, does not work against NPE’s, as they don’t infringe any patents themselves. Nevertheless, a large, dangerous portfolio of patents can be useful when facing attacks from an NPE, as the patents might be traded—in return for the NPE reducing or dropping the case, the NPE could be assigned patents they could use to assert against other competitors.

Think very carefully before asserting patents in this type of marketplace, especially when the company you are attacking has large stockpiles of weapons ready to be fired back at you. Selling the patents to a third-party NPE is a strategy to consider—the NPE undertakes the assertion and the chance of triggering a counter attack might be limited (see Aggression by Proxy, page 25).

34RPX Corporation S1 SEC filing. http://www.investorscopes.com/RPX-Corp/S-1/11340089.asp

35http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2012/04/27/151357127/another-ridiculous-number-from-the-patent-wars

36 Scaling the Patent System, Christina Mulligan, Yale Law School, Information Society Project, Timothy B. Lee, Cato Institute, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2016968

Software Patents & Open Source