Guide to Selling Your Patent & Other Free Resources from Tynax

This document provides a guide helping patent holders understand the process and issues involved in selling a patent. You are advised to look elsewhere for information on selling a company, a product or a developed technology. Some of the points discussed here may not apply to technology transfers and transactions involving the sale of knowhow and intellectual assets other than patents.

GUIDE TO SELLING YOUR PATENT INDEX:

- What are You Selling When Selling a Patent?

- What do Buyers Buy When Acquiring a Patent?

- What Types of Buyers are Acquiring Patents?

- How Does the Buying Process Differ For Defensive v. Assertive Buyers?

- Which Technology Sectors are Most Active?

- What is a Patent Worth and Which Patents are Most Valuable?

- How are Pending Continuations and Divisional Applications Treated?

- How are Families with International Counterparts Treated?

- What is the Process of Selling a Patent--How Long Does it Take?

- Why Set an Asking Price?

- How to Set an Asking Price?

- How do Licensees Affect the Marketability and Value of My Patent?

- How do Liens and Other Claims Affect the Marketability/Value of My Patent?

- What are Claims Charts, and Why Should I Care?

- How Can My Letter to a Buyer Result in me Going to Court?

- Why are Buyers Reluctant to Acknowledge My Patent?

- Why are Patent Attorneys Reluctant to Acknowledge My Patent?

- Why do you Need a Lawyer to Sell a Patent?

- What are the Key Elements of a Patent Purchase Agreement?

- Can I Negotiate a License Back?

- Can I Negotiate an Ongoing Royalty Fee or Licensing Revenue Share?

- What Are Buyers Looking For in the Due Diligence Process?

- Why Do Buyers Request Old Assignment Paperwork and Other Documents?

- Why Do Buyers Ask for Representations and Warranties?

- Why, When and How Do Buyers Investigate Patent Validity?

- Why Do Buyers Often Acquire Abandoned Patents and Applications?

- Why Should I Avoid Selling the Patent Myself?

- Why use a Broker or Intermediary to Sell a Patent?

- How are Brokering Commissions Justified?

- Can I Sell Without Transferring Title?

- How Can I Accelerate the Process of Selling My Patent?

- How Can I Push Up the Value of My Patent?

WHAT ARE YOU SELLING WHEN SELLING A PATENT?

A patent is a right to exclude others from practicing your unique invention. It provides the right to ask the court to force infringers to pay a reasonable royalty and/or issue an injunction preventing future infringement. So, the marketability and value of the patent depends on its infringement status.

You may have noticed that this description of a patent focuses on legal issues and does not include mention of the strength or maturity of the underlying technology. This is because the technology is a different asset to the patent, although the two can be related. When you are selling the patent, you are not selling a right to use your technology, but you are selling the right to prevent others from developing technologies using the patented invention. Understanding this point can help eliminate much confusion surrounding the sale of patents.

WHAT DO BUYERS BUY WHEN ACQUIRING A PATENT?

Buying a patent, the buyer acquires the right to assert the patent against infringers. Of course, if the buyer is an infringer itself, acquisition of the patent removes the possibility of the buyer being sued for infringement.

Technically, as the patent right is purely exclusionary, the patent buyer is not acquiring a right to use the invention itself, as use of this invention may actually involve infringement of another patent. Imagine that the patent covered the design of a bicycle, but each of the components of the bicycle–the wheels, gears, brakes, etc.–were all subject to separate patents held by others. After buying the patent for the bicycle design, the acquirer still does not have the right to build the bicycle as this would involve infringement of the patents for the wheels, brakes and other components involving patents held by others. Of course, the best approach if you want to sell products without fear of patent infringement is to acquire all the patents with inventions forming components–so the bicycle manufacturer is advised to acquire all the patents covering the brakes, wheels and gears along with the patent for the bicycle design. Holding such a complete portfolio, the bicycle manufacturer is able to then make, market and sell bicycles without fear of infringing patents held by others–and is also able to ask the courts to prevent competitors building similar bicycles with similar components.

The bicycle example is useful to understand how patents overlap but is, of course, unrealistically simplistic. In the U.S., there are over 400,000 patent applications each year. With so many patents and applications it is not feasible for a buyer to acquire every patent that might impact its business.

WHAT TYPES OF BUYERS ARE ACQUIRING PATENTS?

As explained further elsewhere in this document, the motivations of patent buyers vary and they acquire for a variety of purposes. However, as a patent is merely a right to exclude others and enforce in court, buyers can be broadly categorized as either assertive or defensive. An assertive buyer acquires patents to enforce against infringers with the view of winning licensing royalties or an injunction preventing future production or distribution of infringing products. A defensive buyer acquires patents they can use in a counter-suit if they are accused of infringing by another patent holder find themselves defending a lawsuit. So, both assertive and defensive buyers acquire patents that they can assert against infringers in court. The difference is merely when and how the lawsuit is triggered.

Assertive buyers generally hire armies of lawyers to file lawsuit and negotiate licensing transactions with infringers. Organizations that assert patents as their primary business activity, and do not make or market their own products have attracted the unfortunate label of patent trolls. However, there are many forms of organizations that assert patents and this activity has been part of the business landscape in the U.S. for decades.

In response to ongoing litigation, defensive buyers are often operating companies that make and/or sell products in the U.S. market. Large product-oriented corporations with deep pockets are the most likely target of the patent asserters, and hence, are the most active buyers for defensive purposes.

Defensive buyers are grouping together and forming patent pools. Patent pools involve several corporations pooling funds to acquire patents that are then licensed to the members of the consortium. Whether these pools are primarily defensive or assertive is not yet clear–they are probably both. The stimulus for joining forces was probably the result of costly defensive litigation, but with growing stockpiles of patents, it is inevitable that the pools see compelling opportunities to assert the patents for profit. Patent pools certainly acquire patents to take them off the market, and out of the hands of assertive buyers, but they likely acquire patents that they can assert themselves.

Assertive buyers, defensive buyers and patent pools form the vast bulk of the demand for patents today. Of the three, patent pools are the most active, defensive buyers second and assertive buyers a distant third in terms of the number of patents acquired.

HOW DOES THE BUYING PROCESS DIFFER FOR DEFENSIVE VS. ASSERTIVE BUYERS?

Assertive buyers often look to draft the outline for a complete infringement lawsuit before acquiring a patent. This can take time and demand a good deal of information from the patent holder. Defensive buyers are usually less selective and the process of evaluation can take weeks as opposed to months.

WHICH TECHNOLOGY SECTORS ARE MOST ACTIVE?

The most active sectors for patent sales are high technology sectors that have seen a good deal of infringement litigation in the past. Buying activity is currently taking place in areas such as wireless communications, telephony, flash memory, semiconductors, ecommerce, Internet and other software applications.

WHAT IS A PATENT WORTH AND WHICH PATENTS ARE MOST VALUABLE?

Unfortunately, many patent holder are misled by unrealistic valuation calculations and their expectations in terms of pricing are unreasonably high. As with any commodity or asset, the value is driven by what a ready and willing buyer is prepared to pay. Some websites and valuation firms unscrupulously prey on inventors and sell valuation reports that appear very appealing but are not driven by actual buying activity.

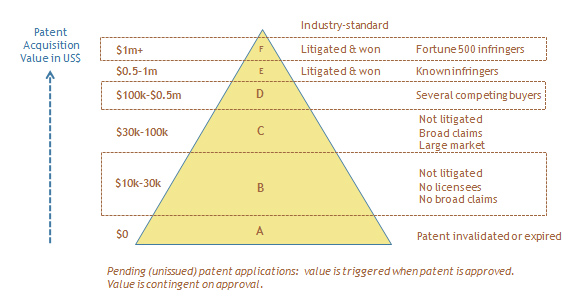

The following valuation reflects actual buying activity seen by brokers in the U.S. and worldwide and include the thousands of listings syndicated on the Tynax exchange. The valuations reflect the sale of a large proportion of the patents sold in the marketplace during the last 12 months. These prices apply to issued U.S. patents.

Group A: Patent Value $0.00

Patents that are expired or otherwise found invalid have no value. As roughly half of litigated patents are found to be invalid by the court, a large number of issued patents fall into this category.

Group B: Patent Value $10,000-$30,000 Per Patent

Valid U.S. patents that do not have particularly broad claims, are not in a particularly large market and have no licensees and have not been litigated.

Group C: Patent Value $30,000-$100,000 Per Patent

If the patents have broad claims or the market is particularly large and growing, then the price of unlitigated patents can increase toward the six figure range.

Group D: Patent Value $100,000-$500,000 Per Patent

Where multiple competing buyers bid to acquire a patent with strong claims with application in a large growing market, the price can rise to several hundred thousand dollars.

Group E: Patent Value $500,000-$1m Per Patent

Generally, the patents that sell for the mid to high six figure range are those that have been litigated and won, and where there are known infringers. The price is justified by the potential royalty stream from such infringers.

Group F: Patent Value S1m+ Per Patent

A patent that has been successfully litigated, is battle tested, with identified Fortune 500 infringers can sometimes bring a price in excess of $1m.

Group G: Industry Standard

A very small number of industry standard patents sell for low to mid seven figure sums. These prices are generally justified by the huge strategic advantage such a patent offers the owner, together with the long term potential royalty stream from infringers/licensees.

Industry standard patents can be found in many high-tech sectors, especially pharmaceuticals and medical/biotech areas.

HOW ARE PENDING CONTINUATIONS AND DIVISIONAL APPLICATIONS TREATED?

Pending patent applications are generally too speculative to justify any value as the patent or some of the claims may never be approved by the patent office. Buyers are usually not interested in acquiring individual pending applications until the claims are allowed and the patent is subsequently issued.

An issued patent can spawn children in the form of continuation and divisional applications. As these applications are not yet allowed by the patent examiners, they are somewhat speculative, however they can add value to the patent. If an issued U.S. patent is sold together with pending continuation and divisional children applications, this can increase the value of the issued patent by 10-25%.

Often a continuation involves broadening the claims of the parent, so buyers are highly reluctant to acquire parents without continuations and these are almost always bundled together in the sale. However, divisional applications are somewhat different from the parent, involving different inventions, so they can sometimes be sold separately from the parent patent.

HOW ARE FAMILIES WITH INTERNATIONAL COUNTERPARTS TREATED?

A U.S. patent is enforceable only in the U.S., a Chinese patent is enforceable only in China and patent rights are generally country-specific. So, patent holders often file for patents on the same invention in several countries. A patent application in one country often provides a priority date for patent applications in other countries, and act something like a parent with international children.

When acquiring a patent, the buyer usually looks to acquire all the international counterparts in the same transaction. This is partly to enlarge the territory that can be covered by the patent, but is also done to remove any doubts about the buyer owning clean title. If the buyer acquires the patent for a country A, but fails to acquire the counterpart for country B, there is a possibility that the ownership of the patented invention could be challenged, especially when the priority date was provided by the country B filing.

A patent with international counterparts is, of course, more valuable than a patent covering only one country. Buyers are mostly interested in U.S. patents today and international counterparts can add 10-25% of the value to a U.S. patent.

WHAT IS THE PROCESS OF SELLING A PATENT--HOW LONG DOES IT TAKE?

On average, like any significant business transaction, the process of selling a patent takes around nine months. The first three months is spent preparing the listing and marketing materials and distributing them out to potential buyers.

The second three month period is spent promoting the listing, providing interested buyers with additional information and negotiating the terms of a potential transaction. On average, terms are agreed with a buyer after 6 months has elapsed–much of this time is taken up by the buyer evaluating the patent, setting a value and negotiating with the seller.

After terms are agreed, the process is in the hands of the lawyers. A patent purchase agreement is prepared by lawyers representing the buyer, this is then negotiated with lawyers representing the seller.

The process of checking for clean title and gathering the document required to close the transaction can take weeks or months, depending on the speed of the lawyers, the number of patents and the complexity of the transaction.

Closing takes place after the lawyers on both sides are satisfied that the documents are complete and payment is transmitted from the buyer to the seller.

WHY SET AN ASKING PRICE?

Patent buyers are wary of sellers with unrealistic pricing expectations. The process of evaluating a patent is time consuming and expensive for the buyer and many are reluctant to undertake this work if they suspect they will be unable to reach a mutually agreeable price with the seller.

Many buyers, certainly many of the most active, experienced buyers, refuse to evaluate and consider a patent until they have assurance that the sellers pricing expectations are reasonable. Of course, they expect some negotiation on price, but a patent with an unjustified multimillion dollar price tag will not be taken seriously by buyers.

HOW TO SET AN ASKING PRICE?

The purpose of setting the asking price is to grab attention of the buyer and set their expectations. As discussed above, setting an unrealistic price will make your patent difficult, if not impossible, to sell.

Sellers should discuss pricing with their patent brokers but the pricing should be within the framework provided above. If you believe your patent is in group F, then provide evidence of prior litigation and claims charts showing ongoing infringement. Of course, setting an asking price a little higher than you are ultimately prepared to accept will provide you with some room for negotiation.

HOW DO LICENSEES AFFECT THE MARKETABILITY/VALUE OF MY PATENT?

The value and marketability of the patent is affected by licenses. The license is usually transferable, the buyer can step into the shoes of the seller and inherit the license arrangements. The effect of licensing on the value of the patent can be positive or negative, depending on the terms of the license. The impact of licensing arrangements depends partly on the nature of the license but also on the buyer and their motivation for acquiring the patent.

A license arrangement is viewed by the buyer as an encumbrance as it affects the buyers ability to acquire clean title. The scope of the license is significant to the buyer as it affects the rights being acquired. A patent that has been licensed under an arrangement where the licensee has unrestricted rights to sub-license is worth very little to a buyer as little other than bare title to the patent is available for sale in this situation.

However, a patent with an ongoing revenue stream from non-exclusive licensees can be significantly more valuable than a patent without licensees. A buyer looking for a revenue stream from the patent will be attracted by such licensing arrangements, but a buyer looking to assert the patent against one of the existing licensees will find this patent of very little value.

For these reasons, when evaluating a patent for acquisition, buyers request information on licensing arrangements attached to a patent and other encumbrances such as liens.

HOW DO LIENS AND OTHER CLAIMS AFFECT THE MARKETABILITY/VALUE OF MY PATENT?

A lien is a claim of ownership on the patent by a lender or some third party to the transaction. As such, it restricts the buyers ability to acquire clean title and can lead to disputes of patent ownership in future. Liens can complicate the transaction and the buyer usually looks to ensure that liens are removed prior to closing of the patent sale. It is important to disclose liens to buyers early in the process so there are no surprises that derail the transaction later on, and the buyer can be assured that the lien can be removed to ensure the transfer of clean title.

WHAT ARE CLAIMS CHARTS, AND WHY SHOULD I CARE?

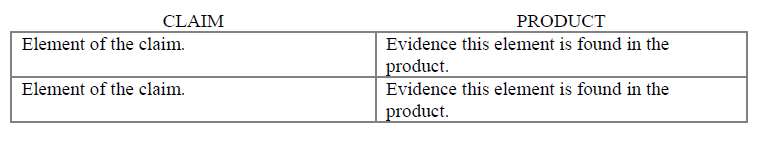

As a patent is merely a right to enforce, to exclude others practicing the disclosed invention, even defensive buyers are looking for patents that can be asserted against infringers. A claims chart is a simple two-column chart that is used to show evidence of infringement.

You should care about this because evidence of infringement is important to establish the value of the patent–a patent with claims charts is more marketable and attracts a higher value than one without.

HOW CAN MY LETTER TO A BUYER RESULT IN FINDING MYSELF IN COURT?

A company receiving a letter, email, or some communication containing a patent number and reasonably perceives that it may be accused of infringing the patent has a right to ask the court for a declaratory judgment–declaring whether infringement is actually taking place. So, a letter informing a potential buyer of your patent could result in the buyer bringing a lawsuit against you requesting such a declaratory judgment. You are then required to file a claim of patent infringement as a compulsory counter-claim and a complete patent infringement lawsuit has been triggered.

Buyers not only have the right to file such a declaratory judgment suit but it is often in their interests to do so. The buyer filing the suit effectively selects the court where it wants the case to be heard. As patents cases are heard in federal court, they can be brought in a variety of states and districts. Its in the buyers interest to bring the case in the district thats most convenient to them, and is most likely to present a jury sympathetic to the buyers argument.

As patent sellers are aware of the multi-million dollar costs involved in patent infringement suits and the danger of triggering a lawsuit when communicating with buyers, the seller often engages an agent or intermediary such as Tynax to communicate with the buyer and remove the risk of unwanted litigation.

WHY ARE BUYERS RELUCTANT TO ACKNOWLEDGE MY PATENT?

If you send your patent number to a potential buyer, it is unlikely that you will receive a confirmation of receipt or any form of acknowledgement. This is because the courts customarily award triple damages for knowing infringement, as opposed to infringement that is accidental. If you put the buyer on notice of your patent and subsequently sue the buyer for infringement, they are liable to pay three times as much in damages as they would if they were unaware of the patent. By responding to your email or letter introducing your patent, the buyer is providing evidence to you that it is on notice of the patent, and this evidence may be used against them in court.

For this reason, it is not unusual for buyers to operate under total silence when evaluating a patent for purchase. If the buyer is interested, they will often inform their broker and request further information. If the buyer decides not to acquire the patent, they generally do not communicate this or disclose that they have evaluated the patent to the seller or the sellers agent.

WHY ARE PATENT ATTORNEYS RELUCTANT TO ACKNOWLEDGE MY PATENT?

When filing new patent applications with the patent office, an attorney has a duty to disclose any other patents that could form prior art for the invention forming the application. Patent attorneys, as a result, take steps to minimize their exposure to any patents other than the ones they are filing for their clients. The attorneys relationship with the patent office is critical to his/her ability to file new patents in future and an attorney that is aware of a patent that might form prior art is duty bound to disclose this information. Breaching this duty and failing to disclose known patents can lead to censure by the patent office and can affect the attorneys career. So, attorneys are reluctant to receive detailed information regarding patents for sale.

WHY DO YOU NEED A LAWYER TO SELL A PATENT?

A patent sale involves intricate paperwork that must be customized for each transaction. The best way of protecting your interests is to have a lawyer with experience in these transactions represent you. The lawyer can structure the transaction in a way that minimizes your liability exposure.

WHAT ARE THE KEY ELEMENTS OF A PATENT PURCHASE AGREEMENT?

The patent purchase agreement (PPA), otherwise known as the patent acquisition agreement (PAA) is generally drawn up by the buyer and includes the following provisions:

- Identification of the patents and assets being sold.

- Purchase price and payment details.

- License back for seller, where negotiated.

- Assignment (transfer) of the patent rights on closing.

- Representations and warranties that the seller owns the patents being sold.

- Representations and warranties that the information provided by the seller is accurate.

- Confidentiality agreement.

CAN I NEGOTIATE A LICENSE BACK?

It is not uncommon for patent sellers to negotiate a license back allowing the seller to continue to use the patented invention. This license is often structured as a covenant not to sue–the seller is free to continue to make and sell products that use the patented invention without the risk of being sued by the buyer for infringement.

The buyer is understandably keen to limit the scope of the license back. As the patent is a right to exclude others practicing the disclosed invention, the buyer must retain control over how the license is transferred and sub-licenses are issued. The license must be non-transferable and sublicensing disallowed, otherwise the rights acquired by the buyer would be virtually worthless.

CAN I NEGOTIATE AN ONGOING ROYALTY FEE OR LICENSING REVENUE SHARE?

A transaction involving an ongoing royalty or revenue share from products using the patented invention makes sense in theory but in practice it is usually impractical to implement and these transactions are surprisingly rare. One reason is that the buyer often puts the patent into a portfolio with a large number of other patents and identifying which individual patent generates revenue is very difficult. Another reason is that the buyer often holds the patent to assert against others, and does not practice the invention in its own products. Of course, monitoring sales, calculating revenues related to a particular patent and reporting of revenues is also an administrative burden on the buyer.

The situations where the buyer is prepared to entertain an ongoing royalty stream and the patent results in a product with sales revenues that can be easily tracked and calculated, are relatively rare but they do sometimes exist, especially in the pharmaceuticals and biotech sectors.

WHAT ARE BUYERS LOOKING FOR IN THE DUE DILIGENCE PROCESS?

A patent buyer is concerned with at least three issues in due diligence. The first, and the most important topic for most buyers is clean title. The buyer wants to ensure that they are acquiring all the rights to the patents and want to avoid claims of ownership from inventors, prior owners, or lien holders in future.

The second issue is patent validity. Some buyers investigate the validity of the patent, usually by checking the file wrapper correspondence with the patent office and searching for prior art. The amount of work conducted here depends on the buyer and their motivation for purchasing the patent.

A third issue investigated by buyers is the validity of the infringement information, when this is provided in claims charts. For assertive buyers, this can be an important part of the due diligence process, and can take some time.

WHY DO BUYERS REQUEST OLD ASSIGNMENT PAPERWORK AND OTHER DOCUMENTS?

Patents are issued to inventors. Inventors can then assign the patent rights to their employers or other parties. Two or more co-inventors of a patent each own full rights to the patent and is able to assign or license the patent rights without requesting approval from the other co-inventors.

Title, ownership rights to the patent, is transferred from the inventor to subsequent parties through assignment. Many re-assignments of rights are not subsequently registered with the patent office, so the public patent records are an unreliable source of ownership information–the owner on record at the patent office is often inaccurate and out of date.

As a seller, you own title to your patents by virtue of either being the inventor or through assignment agreements. The buyer acquiring your rights wants to make sure that you own the patent rights you are selling. Often this involves checking that all the relevant assignments were properly executed.

The chain of title for patents often involves several assignments. The first assignment is often from the inventor(s) to their employer, subsequent assignments take place when the patents are sold or the employer is acquired by another company. If any of these assignments were invalid, the buyer could be acquiring patent rights that do not exist, or could be challenged in future.

If you are selling your patent and you want to speed up the due diligence process, you are advised to gather all the relevant assignment documents as soon as you put the patents on the market, check the signatures are all in place and make these documents available to the buyer as soon as the terms are agreed.

WHY DO BUYERS ASK FOR REPRESENTATIONS AND WARRANTIES?

When the buyer is asked to rely on statements or assurances made by the seller, the buyer is likely to ask for representations and warranties from the seller that the information is accurate. This places a liability on the seller if the information is subsequently found to be inaccurate.

The most likely scenario where representations and warranties are important is where the seller is unable to provide copies of all relevant assignments. The assignment documents effectively provide proof-of-ownership of the patents. If these important papers cannot be provided by the seller, the buyer will often request a representation and warranty from the seller that the seller does indeed own title to the patents that are being sold. This is less than ideal for the buyer, as often the only recourse the buyer has if it is found that they have paid the seller for patents they didn’t own is a refund of the purchase price and this is often insufficient to fully compensate the loss incurred by the buyer.

If you are concerned about liability, you may be able to negotiate the elimination of representations and warranties if you provide the buyer with copies of all the assignments and strong evidence that you own clean title to the patents being sold.

WHY, WHEN AND HOW DO BUYERS INVESTIGATE PATENT VALIDITY?

Buyers are aware that a large number of patents issued by the patent office are later deemed invalid. In fact, something in the region of fifty percent of patents that are asserted against infringers in court are found to be invalid during the litigation process. The due diligence work undertaken by the patent office examiner to investigate validity is not as extensive as that undertaken by the defendant in an infringement lawsuit, as the examiners work on a much more restricted budget than defense attorneys. As a result, patent invalidity is often undetected in the prosecution process and is only discovered in litigation.

The discovery of prior art showing the invention had been conceived earlier by someone other than the inventor, is a common basis for invalidity. Errors in the application process, lack of novelty and errors in the examination process are also grounds for later invalidation.

Buyers understand that the patent they acquire today could be found invalid, and worthless, tomorrow and as a result they often undertake some checks on validity. Lawyers representing the buyer can justifiably spend huge amounts of time and energy researching prior art. However, in most transactions, the checks are intended to uncover only obvious grounds for invalidity by scanning through the communications between the inventor and the patent office. This communication is recorded in the file wrapper that is available from the patent office.

The amount of time and energy spent investigating validity of a patent depends on the price and the total value of the transaction, the reason for buying the patent and the motivation of the buyer. Generally, assertive buyers looking to file infringement suits with the patent spend more time searching for prior art and investigating validity than defensive buyers who often make no more than a cursory check of the patent office correspondence.

WHY DO BUYERS OFTEN ACQUIRE ABANDONED PATENTS AND APPLICATIONS?

Buyers often look to acquire all the international counterparts, parents and children of a patent, even when these patents and applications have been abandoned. This is done to remove any chance of dispute over clean title. If the buyer simply acquires a patent, there’s a risk that the owner of the other family members could dispute ownership of the patent. Abandoned applications can often be revived, or they can be used to claim priority for future continuations and related applications. So, the buyer usually looks to sweep up all related family members when buying a patent, and it is not unusual for the buyer to acquire abandoned and expired patents in the process

WHY SHOULD I AVOID SELLING THE PATENT MYSELF?

Patent buyers are often reluctant to deal with sellers directly, as they are unsure if the approach by the seller is the prelude to an infringement lawsuit or a genuine opportunity to buy the patent. As mentioned above, by sending a letter to the buyer, the seller faces triggering a lawsuit from the buyer for declaratory judgment.

If the buyer is prepared to deal directly with the seller, they are often in position to leverage their size and superior power to negotiate preferential terms.

WHY USE A BROKER OR INTERMEDIARY TO SELL A PATENT?

Buyers shield themselves from potential infringement liability by working through agents and various forms of intermediaries. Brokers and intermediaries like Tynax are able to reach these buyers and have patents opportunities evaluated without triggering the potential for litigation. Having open channels to the key decision making buyers is an essential component of the sales process.

The broker is taken seriously by the buyer and has the experience to navigate the intricate steps in sales process. By reaching a larger number of buyers, the broker is often able to create an auction environment and negotiate higher prices than the seller could when promoting the patents directly.

HOW ARE BROKERING COMMISSIONS JUSTIFIED?

Patent brokers have traditionally operated under a similar model to contingency lawyers. The broker representing a seller receives nothing if the patent is unsold, but receives a 33% commission upon closing of a transaction. As with contingency law firms, there are variations on this model and the commission varies from broker to broker and transaction to transaction between 25% and 50%.

To observers coming from the real estate brokering market or mergers and acquisitions, these commission levels may appear high. One reason for the difference in commission structure is that the patent market suffers from a lack of liquidity. By adjusting the price, real estate agents are usually able to sell a property. Lowering the price is not always well received by the seller, but it usually results in a real-estate sale. The same is somewhat true for the sale of businesses, but the value of the transaction here is also usually much higher than the value of a patent sale. Lowering the price of a patent is not a sure-fire method of making a sale and many patents are simply insufficiently appealing to buyers.

The patent broker often shares commission among various co-brokers that also play a part in the transaction. The lack of liquidity in the patent market, the complexity of transactions, syndication costs and revenue sharing among co-brokers means that patent brokers need relatively high commission levels to operate successfully.

CAN I SELL WITHOUT TRANSFERRING TITLE?

Sellers such as universities and research laboratories that have received funding from government or other sources are often restricted from selling the patent outright. However, they are able to license the patents that form the fruit of these sponsored development projects.

As the patent is merely a right to exclude, a right to assert against infringers in court, this is what the buyers are looking for when they acquire patent rights. A transaction can be structured whereby the seller retains title to the patent, but the buyer acquires an exclusive license with right to enforce in court. The right to enforce is usually accompanied by a right to join the patent holder in the action, which itself is accompanied by indemnification that the buyer will pay all the legal costs associated with such enforcement.

With this structure, the patent holder is able to retain title, but sell the substantial rights that a buyer needs.

HOW CAN I ACCELERATE THE PROCESS OF SELLING MY PATENT?

The best way of increasing momentum in the transaction process is to engage with several competing buyers, gather the assignment documents and claims charts before they are requested by the buyer and actively manage the legal process assigning responsibilities and setting deadlines.

HOW CAN I PUSH UP THE VALUE OF MY PATENT?

The value of the patent can be increased by preparing compelling claims charts showing evidence of infringement, reaching out to a number of competing buyers, and providing materials that justify the asking price. A broker like Tynax is often able to provide guidance in these areas and significantly increase the value by creating a bidding environment among several buyers that leads to higher prices.